A Ten-step Introduction to Concordancing through the Collins Cobuild Corpus Concordance Sampler

Table of Contents

2. Getting started: find a word

3. Searching for lemmas and word families

8. Collocation

10. Further study

1. Introduction

If you are a student of English, a teacher, a translator or if you are writing in English, analysing English, or have any questions about how English works, concordancing can be of great benefit to you.

This mini-course is designed to introduce

concordancing to students and teachers, native and non-native speakers of

English and people with a general interest in language and learner autonomy. It

is therefore casting its net over a wide range of people. It does not assume a

great deal of linguistic knowledge: all required terminology, both in computer

use and linguistics, is explained as it is introduced. The main purpose of these sessions is to

introduce the techniques involved in searching for answers to questions.

Just what can be asked will be revealed at every step, as we see how

searches can be formed and refined.

This first Session is a short introduction. In Session 2 we will dive directly into concordancing using the Collins Cobuild Corpus Concordance Sampler. This has been chosen because it is readily accessible through the internet and because of its rich variety of functions that demonstrate many features of full concordancers. Throughout these sessions it will be shortened to CCS.

If you are a non-native speaker of English, it is likely that you will want your English to be as close as possible to the norms of English. You might even think that English is spoken and written with so much variation that the norms are too unstable to be grasped. There is, of course, a core language which represents the vast majority of English, without which it could not be called one language. It is not always easy to gain access to those norms, i.e. the most likely way a native speaker would express something, and grammar books are not always able to answer questions, especially about word use: modern dictionaries, based on corpus research, provide more reliable information. Corpus-based grammar books now exist also, but so far, they are of more use to the language professional than the general user. One of these is the Longman Grammar of Written and Spoken English. Read a review of it in TESL-EJ.

What is Cobuild?

It is an acronym: Collins Birmingham University International Language Database. A great deal of pioneering work in corpus linguistics has been done at Birmingham University. Chris Allen gives an overview of the project from an insider’s point of view:

What

is a corpus?

What

is a corpus?

A collection or body of texts in electronic form. The plural is corpora. The Cobuild corpus is referred to as The Bank of English. This link outlines their project and concludes with a link to the Sampler, which is what the current site is about.

What is a concordancer?

Software for looking into a corpus.

What is a concordance?

The lines of text illustrating the search word, the node.

A caveat for a corpus

A corpus is assembled by collecting texts in electronic form. The texts are usually chosen to represent such things as:

|

genre |

contract, letter of appointment, theatre program |

|

domain |

the family, at work |

|

register |

conversation, fiction, newspaper language, academic prose |

|

mode |

writing, speaking, gesturing |

Importantly, texts are not

corrected according to any grammar or spelling rules, taboo words are not

“cleaned up”, and general abuse of the language sits happily alongside general

use of the language. Slips of the tongue, pen and keyboard remain

intact. It is therefore a descriptive sample of the language, not a prescriptive

one: this makes it rich, but it also means that you should usually look for

significant patterns, not oddities. More on this later.

Importantly, texts are not

corrected according to any grammar or spelling rules, taboo words are not

“cleaned up”, and general abuse of the language sits happily alongside general

use of the language. Slips of the tongue, pen and keyboard remain

intact. It is therefore a descriptive sample of the language, not a prescriptive

one: this makes it rich, but it also means that you should usually look for

significant patterns, not oddities. More on this later.

A caveat for a sampler

In this Sampler, a database of millions of words is searched and up to forty concordance lines are shown. In a full concordancer, for example Microconcord (by Tim Johns and Mike Scott) which has its own corpus of only 2 million words, and the British National Corpus of 100 million words, you find:

|

|

Microconcord |

BNC |

|

hand |

459 |

33484 |

|

grant |

81 |

7594 |

|

unemployment |

120 |

6409 |

|

university |

225 |

16316 |

Somewhat more than forty! Further machine intervention is required when you have large numbers of finds. From an introductory point of view, the forty lines limitation is a manageable number to deal with. And there are techniques for refining your search to get forty sharply focused lines, as we shall soon see.

When forty lines are shown, however, it is not clear how many they were selected from. For example, if you are comparing the use of “at least” and “at the least”, knowing their relative frequencies would be a useful starting point since frequency is an indicator of typicality.

|

|

CCS |

Microconcord |

|

at least |

40 |

662 |

|

at the least |

34 |

1 |

Ultimately, a sampler can answer the question: is there any evidence for…?, rather than a more decisively-framed question.

Non-native

students learning English

Non-native

students learning English

Data Driven Learning refers to studying English by isolating patterns that occur in real language. The student answers his or her language questions by analysing the data the concordance produces. The remainder of these sessions shows just how that is done. These procedures were pioneered largely by Tim Johns who named this pedagogical application Data Driven Learning. Links to some others involved in this form of language study appear throughout these sessions.

One last caveat

Since you have got this far, let me close the introductory session with another caveat, this time for this website. You are reading its first version before it has even been tried out on anyone. Therefore, all comments and suggestions will be gratefully received, read and taken on board. My contact: thomas@fi.muni.cz.

2. Getting started: find a word

Without further ado, let’s jump in head first and see. We will now perform some searches and see what a concordance is, and what concordancers look like.

Note: if you click on this link, Cobuild, you will open the CCS in this window, leaving this one.

There are two alternatives:

(a) using the right mouse button, choose to open the link in a new window, or

(b) Ctrl N will open another window and you can click on the link.

At the bottom of the screen you have the navigation buttons that take you from one window to another.

The Cobuild link is to this address: http://titania.cobuild.collins.co.uk/form.html

Search One

Is whose used with animate and inanimate antecedents.

Type the word whose into the box and click Show concs. The search word is referred to as the node. And the format in which the search results are displayed is referred to as KWIC, which stands for Key Word In Context.

So, do we say, I saw a car whose owner … ?

Search Two

Type the word step into the box and click Show concs.

What do you notice about the order of the first words to the right of the node?

Correct! They are in alphabetical order, with numbers, punctuation and codes (e.g. [f]) at the top. In this concordancer sampler, this is the only possible order to view the concordances in. In other programs, sorting by the first word to the left is one of a number of possible sort options. Each sort reveals different information.

Observation: does the node appear with its declensions or conjugations? See Morphology below.

What do the forty lines of step tell you about the word? What properties of this word can you observe?

· a verb (finite or infinite or both?)

· in a phrasal verb construction

· in a delexical verb construction

· as a noun – with different meanings (polysemy)

·

as part of a compound noun

· common words following it

· commons words preceding it

· in fixed phrases

· in a metaphorical sense

All of this can be demonstrated with this simplest of searches with only forty lines. By this stage you might be wondering what a word is. Click this link for an introduction to the quandary.

Search Three

We might expect that X proves Y in a legal or scientific sense. What evidence do you find for that assumption? Type in prove or proves and click Show concs. Read the contexts observing the sorts of things than can be X (the subject) and Y (the object).

Search Four

Can you pretend something, i.e. a noun or a noun phrase? Can pretend be followed by “-ing” forms, infinitives with or without “to”, “wh-” clauses, “that” clauses, or anything else?

To find out which of these complementation patterns pretend has, type pretend into the box and click Show concs.

What do you notice about this verb when displayed in the KWIC format?

And what mostly precedes it? Modals, auxiliaries and “to”. This is because the word form pretend is uninflected. The full lemma is pretend, pretends, pretended, pretending.

Consider why this information is useful?

Search Five

Question: what parts of speech (POS) can fast function as?

Type the word fast into the box.

Can you say which lines exemplify which POS and how many of each?

|

line numbers |

totals |

|

|

Noun |

|

|

|

Verb |

|

|

|

Adjective |

|

|

|

Adverb |

|

|

This is indicative of the random sampling.

Search Six

Question: Many present participles (-ing forms) are used adjectivally. Is this true of pretending? If so, attributively and predicatively? These are important questions when studying vocabulary.

So far, we have been generating concordances for base (uninflected) forms. But if you want to search for pretending only, type in precisely that. It appears in verb groups (e.g. present continuous) and as an adjective. In Session 4, we will see how to focus such a search.

Search Seven

Comparing how we use singular and plural forms of nouns can be instructive. Try a search on hand and another on hands. What do you notice about the different usage?

Search Eight

If you haven’t already encountered problems using capital letters, try searching for the BBC. Is it possible that there is no mention of the BBC in a corpus of 56 million words? No. It only works if you use lower case letters, i.e. bbc. Similarly, People, is not a valid search, whereas people is, and the results include People.

Search Nine

Try typing in a number and searching. No luck? You have to use a backslash before the number, e.g. \1970 or \12.

Closing comment: it cannot be denied that the language which appears when corpora are searched is noticeably richer than composed, edited or carefully selected examples, for inclusion in textbooks and dictionaries. This richness is an important factor in learner input.

3. Searching for lemmas and word families

The traditional hierarchy of morphology

Lemma

A lemma is a group of words created through inflectional processes – the yellow half.

How many word forms does a regular verb consist of?

worry, worries, worrying, worried.

How many word forms does an irregular verb consist of?

cut cuts cutting

bring brings bringing brought

sink sinks sinking sank sunk

How many word forms does a regular adjective consist of?

steep steeper steepest

Fortunately, you don’t have to enter the full lemma to find it. Simply type @ after your word.

Try searches on precede@, contribute@,

fast@, knife@, corpus@, simple@

Word Family

A word family is a group of words created through word formation processes– the blue half above. It is less precisely determined than the lemma. Use the wildcard symbol (the asterisk) to find any string of letters that follows what you enter. [JET1]

|

preten* |

|

|

prohib* |

|

|

argu* |

|

Since the wildcard finds anything starting with your entry, a search such as mid* or mon* will return quite various results. Try it.

For observing prefixes at work, you could search mega*, under*, mis*, etc. Unfortunately, it is not possible in the CCS to search with wildcard first, e.g. *ness, *wise, *fold, *ish.

4. Parts of Speech searches

Every word in the CCS has its part of speech (POS) marked, or tagged. You can imagine that tagging every word in a multi-million word corpus is a daunting job. In fact, it is done by computers with an estimated accuracy rate of 95%. Being able to search for a word by POS is often essential. For example, the word form ROSE can be a flower or the past tense of rise. Mixed search results will not be helpful.

Some POS issues have been deliberately avoided in CCS, such as the use of some participles as adjectives: winning is not marked as an adjective in “winning smile” and failed is not marked as an adjective in “a failed bank”, but homing is in “homing device”. Also above and fast cannot be located using the adverb tag. Nevertheless, it still provides a view on language that I couldn't imagine finding out about in any other way (apologies to Jan Svartvik).

As we noted in Session 2, fast

can be a noun, verb, adjective and adverb. Being able to specify a search

word’s POS allows you to find a word in more specific contexts and in a more

specific sense. If you were wondering whether to use the adjective fast

or quick in a particular situation, you would obtain more useful data by

specifically searching for the words as adjectives. Search for fast/JJ

and then search for quick/JJ.

As we noted in Session 2, fast

can be a noun, verb, adjective and adverb. Being able to specify a search

word’s POS allows you to find a word in more specific contexts and in a more

specific sense. If you were wondering whether to use the adjective fast

or quick in a particular situation, you would obtain more useful data by

specifically searching for the words as adjectives. Search for fast/JJ

and then search for quick/JJ.

The query syntax is: the word, a slash and the tag in CAPITAL LETTERS.

Here is list CCS POS tags. Other corpora have different tags, and other concordancing programs have different ways of forming a query.

Table of POS tags

This is an expansion of the information provided on the Cobuild site below the concordance entry box.

|

a macro tag: stands for any noun tag |

walk/NOUN |

|

|

a macro tag: stands for any verb tag |

dog@/VERB |

|

|

NN |

common noun |

peer/NN |

|

NNS |

noun plural |

needs/NNS will not show the word as a 3rd person singular verb. |

|

JJ |

adjective |

sound/JJ not as a verb or noun. |

|

DT |

definite and indefinite article |

This is used in word strings, as we shall see in Session 6. It gives a, an and the. |

|

IN |

preposition |

This is used in word strings, when you want a word plus preposition. |

|

RB |

adverb |

Is there an adverb derived from prohibit? prohibit*/RB Or from ration*/RB? |

|

VB |

base-form verb |

trigger/VB or impact/VB |

|

VBN |

past participle verb |

read/VBN – useful if studying passive or perfect aspect. And you can separate out adjectival uses. |

|

VBG |

-ing form verb |

read/VBG – useful if studying continuous aspect. And you can separate out adjectival uses. |

|

VBD |

past tense verb |

set can be present and past. set/VBD only shows concordances where it is a past tense verb. |

|

CC |

coordinating conjunction |

e.g. and, but |

|

CS |

subordinating conjunction |

e.g. while, because |

|

PPS |

personal pronoun subject case |

e.g. she, I |

|

PPO |

personal pronoun object case |

e.g. her, me |

|

PPP |

possessive pronoun |

e.g. hers, mine |

|

DTG |

determiner-pronoun |

e.g. many, all, both, some |

Note: these POS tags become much more powerful when used in combination as we see in Session 5.

Refining your searches

You can now refine the searches you tried in the previous session.

Lemma:

Try a search on peer, which is a

proper noun, and has two meanings as a common noun. It is also a verb. Try peer@.

Try peer@/NOUN and peer@/VERB

Word Family:

Try preten*/JJ. and see adjectives starting with “preten”.

Try prohib*/RB and you will see the derived adverb.

Try contra*/NNS and you will see quite a few nouns in the plural that start this way.

What nouns are in the contract

family? Try contract*/NOUN

What adjectives derive from oil? Search oil*/JJ.

What adjectives derive from club? club*/JJ

5. More than one word

If seeing specific word groups in context would answer your question, type in each word with a + between each word, and no spaces. For example knife+and+fork.

|

L e x e m e |

phrasal verb |

take off, step down, enter into |

|

modals |

be about to, had better, be bound to |

|

|

compound noun |

coffee table, step son, word family |

|

|

|

compound preposition |

away from, regardless of, in comparison with |

|

|

fixed phrase |

in the light of, open to suggestion, up up and away |

|

|

collocation |

vivid imagination, irresistible temptation, little imp |

|

|

idiom |

storm in a teacup, bull in a china shop |

|

|

quotation |

much ado about nothing, couldn’t give a damn |

|

|

discourse markers |

be that as it may, comparatively speaking, in other words |

POS tags can also be part of a search. Try impact+IN to find what prepositions follow impact. More specifically, you could try impact/VERB+IN.

Discontinuous groups

Many phrasal verbs are used discontinuously, i.e. other words appear between the verb and the particle. Add the maximum number of intervening words you want in your search. For example take+3for, or take@+3for.

Delexical verbs are almost always discontinuous. Search give+3smile, make+3speech, take+3photograph, have+3bath.

Does whether or not appear as a fixed unit, or can it be separated? Search whether+or+not and whether+5or+not.

Honing in

It will also happen that after searching a single word, you will want to find more examples of one of the groups in which it occurs. When you search for teach, the second last line contains teach you how to.

Search for the whole chunk.

|

teach+1how |

many lines of teaching someone how to do

something |

|

teach+PPO+how |

gives examples where the object is

a pronoun |

Practice: search the left word and then one of the chunks in which it turns up.

|

mouse |

è |

cat and mouse |

|

table |

è |

table talk |

|

pause |

è |

pregnant pause. |

Alternative search items

If you want to search for two items at the same time, use the vertical bar | (Shift + the key beside the arrow at the top right of the English keyboard).

Ø criticize|criticise

Ø dove|dived

Ø though|although

Ø precision|preciseness

Ø open+2up|out

Training in combining queries

Do we say on a/the train or in a/the train? Since a/the is not at issue, search in+1train and then on+1train. Unsurprisingly, we say both, and equally unsurprisingly, they mean different things. You could limit your search to finding only articles between the preposition and the noun. on+DT+train. Or if you want them on the same screen in|on+DT+train. With a maximum number of forty finds, this can sometimes present too few results.

Is train also a verb? train@/VERB Does it ever have the railway sense when used as a verb? What is the verb that occurs frequently with in train? What compound nouns does train occur in?

Alternatives to POS tags

We noted above that participles were not always marked as adjectives. We know that adjectives typically precede nouns so searching for welcoming+NOUN is likely to find welcoming as an adjective, but it also finds it in the continuous sense e.g are welcoming. Since noun phrases are often launched by determiners, DT+welcoming+NOUN is more likely to prevent any continuous uses appearing.

To search for any –ing form before a specific noun, e.g. ceremony, you would search DT+VBG+ceremony. Similarly, DT+VBN+house will find past participles as adjectives. This is a useful strategy for finding specific types of collocations.

Apostrophes

The plus sign is also used when searching

for words with apostrophes, e.g. can+t, michael+s. The query to find examples of "Bob's your

uncle" is bob+s+your+uncle

6. Searching for patterns

As we have seen, POS queries are not limited to specifying a word’s POS. This allows you to search for a word or lemma in conjunction with a POS. The following sections are designed to illustrate how you can obtain results that illustrate a word’s patterns using different queries

Take AIM as an example.

Follow these

searches through and check your finds against these observations.

|

aim+NOUN |

aim as common noun, proper noun and verb |

|

aim/VERB |

as a verb, aim most

frequently appears with prepositions. |

|

aim/VERB+NOUN |

the base form aim is not

frequently used |

|

aim@/VERB+NOUN |

this search shows more examples of

aiming at something |

|

aim@/VERB+DT+NOUN |

since noun phrases typically start

with a determiner, this search yields the most results of aim’s objects |

|

aim@/VERB+1NOUN |

this shows the random selection of

things that can appear between the lemma aim and a noun. |

|

aim@/VERB+1DT+NOUN |

a combination of the two searches above. |

|

aim@/VERB+IN+DT+NOUN |

this shows prepositional phrases

that follow aim |

|

|

we saw in the above step that at and for were the most frequent. Towards, in and of occurred only once each. Are they so insignificant, or is that a result of the random selection or tagging errors? |

|

aim@/VERB+of aim@/NOUN+of |

A tagging error. When aim

is followed by of, it is a noun |

|

aim@/NOUN+of |

What are the structures here? 1. One structure is of with

an –ing form. 2. The aim of X + to be (without

to) + infinitive (with to). |

|

aim@/NOUN+of+VBG |

For more examples of 1. |

|

aim@/NOUN+of+2NOUN+be@+to. |

For more examples of 2. |

|

NOUN+of+2NOUN+be@+to |

Try this search and see if this

structure is unique to aim. |

|

aim@/VERB+to |

When do we say aim to? When

to is part of the infinitive. So now we have observed that aim

is also followed by the infinitive with to. |

|

aim@/VERB+to+DT+NOUN |

Does to launch

prepositional phrases? |

|

aim@/VERB+in |

In the examples found here, in

is not bound to aim, rather it launches a prepositional phrase. |

|

aim@/VERB+towards |

Four finds is not many. Is there

another way of expressing that concept? |

|

aim@/VERB+for |

Do aim for and aim

towards express the same thing? Have a look at the for list and

consider where towards could be substituted without changing the basic

meaning. Unlikely! |

|

take@+aim |

this delexical form seems to be

restricted to the target sense of aim. |

Grammar patterns

In English, perfect and continuous aspects, the passive, causative and conditionals are formed by auxiliaries in contrast to many languages where they are formed with suffixes. Auxiliaries are words, and this is what concordancers work with best.

What structures will the following queries exemplify?

have|has+been+VBG |

|

|

had+been+VBG |

|

|

have@+be@+VBD |

|

|

have@+PPO+VBD |

|

|

get@+VBN |

|

|

have@+PPS+ever+VBN |

|

|

if+1had+VBD+6would |

|

|

if+PPS+4will |

|

Active voice: how active?

When is get used to form the passive? get@+VBN or get@+1VBN will provide some examples that could support your hypothetical answer to this question. It is necessary to separate the constructions in which get is a full verb meaning obtain or become etc from those where it is an auxiliary. How? Human intervention, i.e. do it yourself.

See The Get Passive for an English lesson on this issue.

Curious and Curiouser

Did you know that stative verbs cannot be used in continuous structures? Go to this grammar link for a statement of the rule. For a longer list of examples, have a look at netgrammar. What if you came across one of these verbs used continuously? Would you doubt the rule? How can we find evidence to support or refute it?

Try be+VBG or be@+VBG.

Search for some of the examples given at those sites. e.g. be@+hating, or since continuous forms are often discontinuous (sic) be@+2owning.

Colligation

The above section referred to grammar patterns in the abstract, as the foundation of clauses. The more familiar concept of collocation, as we shall see in detail below (Session 8), refers to frequent co-occurrences of words, e.g. logical conclusion, end result, to answer a call. Colligation, however, refers to a word’s syntactic patterns, which is an important part of knowing a word. In Barnbrook’s words, colligation refers to collocation patterns that are based on syntactic groups rather than individual words (1996).

Very interestingly, corpus analysis has shown that words with the same complementation can be grouped into semantic classes. For example, when bleed, care, cry, fear, feel, grieve, mourn and weep (Levin 1993:192) are followed by for someone, they express sympathy. When these words have different complementations, they do not form this group.

For a solid introduction to this notion, go to the Forum section (p.3) of this link by Susan Hunston.

Which verbs can you find that have the following structures? Can you see any semantic similarities within each pattern? Try the following:

|

VERB+NOUN+as+JJ |

|

|

VERB+on+to+NOUN |

|

|

it+VERB+to+VB |

|

|

VERB+from+NOUN+to+NOUN |

|

|

draw+2NOUN+from |

|

Articles – using

DT in queries

Is it true that polar adjectives tend to be preceded by the definite article?

Search DT+first|next|last and compare your findings with a+first|next|last.

Right and Wrong

*This is

the best way how to learn English. (The asterisk is a convention used in

grammar books to indicate that a sentence is unacceptable). Unacceptable? Try

this procedure:

|

way (or way@) |

gives an overview of what

typically follows the word. There are

two ways of complementing way with a verb: of + ing form and infinitive

with to. |

|

way+how (or way@+how) |

of all the concordances, only one

has this use of way how. |

|

way+of+VBG |

convincing results |

|

way+to+VB |

convincing results |

Decisions

decisions: when to use the infinitive and when to use the gerund?

Correct?

Which is correct: it is me or it is I? Search be@+me and be@+i. Don’t forget that we do not use capital letters in queries except as POS tags. Alternatively you could search: it+be@+PPS and it+be@PPO.

What does “correct” mean? What does hypercorrect mean?

7. Language varieties

Whole texts are tagged according to variety and other specifications. Corpora designed for research into stylistics or pragmatics, for example, are likely to be tagged in great detail and include the age, gender and nationality of the speakers, the date of publication, etc.

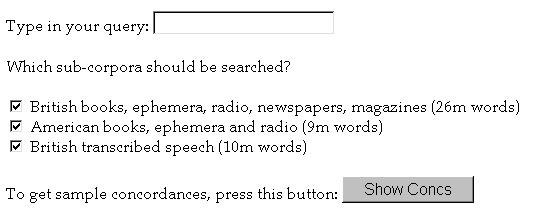

In the CCS, you have three choices, namely:

q British books, ephemera, radio, newspapers, magazines (26m words)

q American books, ephemera and radio (9m words)

q British transcribed speech (10m words)

If restricting the text type according to these criteria could be helpful, select the appropriate check boxes before hitting Show Concs.

Spoken and Written Language

You might like to read this introductory article by Mario Rinvolucri, Distinctions and Dichotomies on spoken and written language.

Ø Are moreover and whereas used in speech, or do they belong to the written language?

Ø would have thought – is this lexical bundle used in written English?

Ø You can find examples of question tags, can’t you?

Ø Are goodness me, for+all+i+care and for+heaven+s+sake actually used?

Ø

This spoken search may surprise: like+VBD

UK and US English

Ø Who says: different from and different than.

Ø

Dived

or dove? Also, incidentally, Dove/VERB vs dove/NOUN

Ø Some say have, others take a bath or shower. Try this: have|take+DT+bath|shower

How are these words used differently on opposite sides of the Atlantic?

Ø

momentarily

Ø

smart

Ø

fancy

Ø football

In which language variety does lanai

appears as a common noun? And Hoosier? This

link will take you a discussion of the word – where you will also see “unhandy”

in its definition.

For more on these varieties, try "Or whose language is it anyway?" and

Potentially Confusing And Embarrassing Differences between American and British English.

Exploiting the varieties function

Do we write the 1970s with or without an apostrophe? Remember to use the backslash before numbers. Perform these two searches and note how many concordances there are of each: \1970s and \1970+s. If there are less than forty, we can assume that there are no more in the whole corpus, and that that number out of 56 million words is not very significant. Search \1970+s as US and again as UK. Does it seem that these are all the examples in the whole corpus? Search for \1970+s as transcribed speech only. What do transcribers know about writing decades with apostrophes?

8. Collocation

The tendency for lexical words to occur together is called collocation, e.g. a vivid imagination, perform an analysis, deliver a speech, a problem child, rotten lover. But not all co-occurring items can be counted as collocations. The following are not collocations:

Ø Multi-word lexemes are not collocations, e.g. phrasal verbs, compound nouns

Ø Colligation e.g. rely on, wait for,

crowd of, can’t help + -ing,

Ø Lexical bundles e.g. I don’t know, at the time of writing, it is interesting to note that, to be taken into a account

Ø Fixed phrases may be considered an

extended collocation: e.g. rather you than me, if you’ve got the energy, not

on your life, all’s well that ends well, under the weather, the nine o’clock

news, not for love (n)or money, as far as I’m concerned,

Collocation is a major issue in current linguistic thinking and its applications to language learning and translation, in particular. This is partly because a sound knowledge of collocations brings language production closer to native speaker norms. Firth said in 1957 that you know a word by the company it keeps. For Cobuild’s purposes here, and on their Collocations CD, the company a word keeps is specified within four words to the left or right of the keyword (or node). In other concordancing programmes you can control this range.

First collocations search

Enter government into the Collocation Sampler. Click Show Collocates. It looks through the corpus and produces a list of the 100 most frequent words, and you will notice that many of the words are “government-type” words.

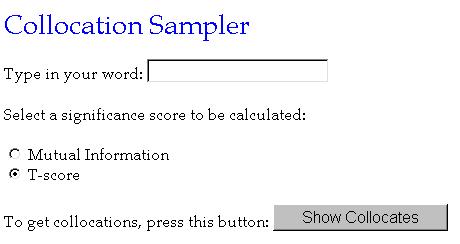

T-score and MI score

Enter experiment into the Collocation Sampler and choose T-score. Click Show Collocates. Open a new window and repeat this search choosing Mutual Information. You will notice that the results are quite different. T-score or MI score which are statistical statements of probability and significance of co-occurrence.

Here

is a brief summary/extract of the information Cobuild provides at this site:

Raw freq often picks out the obvious collocates ("post office" "side effect") but you have no way of distinguishing these objectively from frequent non-collocations (like "the effect" "an effect" "effect is" "effect it" etc).

MI (Mutual Information) will highlight the technical terms, oddities, weirdos, totally fixed phrases, etc ("post mortem" "Laurens van der Post" "post-menopausal" "prepaid post"/"post prepaid" "post-grad").

T-score will get you significant collocates which have occurred frequently

("post office" "Washington Post" "post-war",

"by post" "the post").

Note: If a collocate appears in the top of both MI and T-score lists it is clearly a humdinger of a collocate, rock-solid, typical, frequent, strongly associated with its node word, recurrent, reliable, etc etc etc.

For the full information that Cobuild supplies, click on the underlined column headings at the top of the collocations list at their site.

Further refining your collocations searches

You can

refine your collocations in similar ways to your concordance queries. For

example, all of the following will yield different results, and you need to

consider what you are looking for. Try the following searches as collocations

searches.

|

grant |

You see that both refuse

and refusal appear quite high in the list, which might also be

considered from a real-world point-of-view. |

|

grant@ |

the lemmas of the noun and the

verb |

|

grant/NOUN |

|

|

grant@/NN |

Since General Grant and Hugh Grant (hard

to find links that don’t have pop-ups) occur frequently in the literature,

there is some advantage to restricting your query to the common noun. |

The

statistics can be very revealing, but the collocation list produced is often

best considered a starting point. Select what is of interest there and return

to the concordancer. For example, how do refuse and grant

collocate? Try the following as

concordance searches:

|

refus*+4grant |

without searching for grant

as a noun, you get refuse to grant someone something. |

|

refus*+4grant/NN |

the wildcard (*) allows the inclusion of the word family and the lemma. |

|

grant@/NN+4refus* |

CCS’s list does not distinguish

left and right collocations, so both need to be checked. |

Collocations and synonyms

What are

the differences between great, grand, big and large? This is a

“great, grand, big and large” question in which collocations play some role.

Part of the answer to “what’s the difference between” can often be found in the

word’s collocations.

Consider which of the following four adjectives collocate with the nouns in the left column. You might find yourself indicating some of them as strong (S) and weak (W) collocations rather than an absolute Yes or No. The nouns were chosen from the T-score collocations list for each of these adjectives, so you can check your responses yourself.

|

|

great |

grand |

large |

big |

|

asset |

|

|

|

|

|

brother |

|

|

|

|

|

difficulty |

|

|

|

|

|

effect |

|

|

|

|

|

event |

|

|

|

|

|

extent |

|

|

|

|

|

fun |

|

|

|

|

|

house |

|

|

|

|

|

idea |

|

|

|

|

|

impact |

|

|

|

|

|

majority |

|

|

|

|

|

opera |

|

|

|

|

|

picture |

|

|

|

|

|

pleasure |

|

|

|

|

|

population |

|

|

|

|

|

problem |

|

|

|

|

|

quantity |

|

|

|

|

|

question |

|

|

|

|

|

scale |

|

|

|

|

|

success |

|

|

|

|

|

tour |

|

|

|

|

As

mentioned above, collocation plays some role in answering “what’s the

difference”, but most of these nouns allow more than one of these adjectives.

Sometimes they form a chunk, e.g., great grandfather, grand prix,

Grand Canyon, (in) large measure, (to) great effect.

Big

brother and big

bang are chunks when preceded by “the”

e.g. … 4,000 million

years since the Big Bang which created the earth's …,

and a

collocation when preceded by “a”.

e.g. The next thing I heard

was a big bang.

And

there are metaphorical uses too,

e.g. … transformed

by deregulation - the Big Bang . This brought in competition …

You might like to look up Big brother and big picture in the same way.

Try the

same approach on another set of synonyms, for example, demonstrate,

establish, prove, show. There is a most excellent online resource from Vancouver Wordnet that

can be consulted in this connection.

Collocations and polysemy

We have already seen some examples of polysemy, that is, words with more than one meaning. Sometimes a word may collocate with one of a word’s meanings and not with another of its meanings. The noun race has two very different meanings. Search for its collocations and note which words collocate with which meaning:

|

contest |

|

|

ethnic group |

|

Another example is horse which has quite different collocations depending on its reference. Search of its collocations and note which words collocate with which reference.

|

agriculture |

|

|

gambling |

|

|

sport |

|

These considerations are important when you generate collocation lists.

Collocations and connotation

Yet another

factor in “what’s the difference between” lies in connotation, which you

can find briefly described at Denotation and Connotation.

When would you choose to describe someone as fat, obese, overweight, dumpy or

corpulent? They are synonyms in as far as they carry more or less the same

information, but they do not express the same attitude.

As we saw in Collocations and Synonyms, some pairings are just a fact of life.

As we now see, some pairings are a purposeful choice.

Search: What mongers do we have in English? Search monger. Search mongers. Search monger* and see how different the results are. Do mongers have positive, negative or neutral connotations?

Search galore or arch+NOUN for further examples of positive and negative charging.

Other Searches

What verbs are used with hypothesis, if not prove? Are any of them synonymous with prove? Do confirm/corroborate/bear out or other words similar to prove appear in the lists?

Further Reading

For a pedagogical discussion of Collocation read Jimmie Hill.

9. Searching for Answers: you have to have a question

As you have seen, the searches we have been doing throughout these sessions have been motivated by a question. And many of these questions are typical questions that arise when one is producing language (i.e. speaking and writing). You might like to consider how else you can find answers to these questions without accessing a corpus.

Now that you know what the search results look like and have some idea of the information they reveal, you can start to consider how you will formulate your questions.

Interpreting results

As mentioned above, a search that returns fewer than 40 concordances suggests that what you are searching for is not very significant. While it is true that frequency is an indicator of typicality, …

But the purpose of the search has to be borne in mind. Are you looking for typicality or just some examples that it exists in English at all?

From another angle, you must also take into consideration that a single appearance of something among forty concordances could be significant. It is necessary to isolate it and search it directly. For example, VERB+2hypothesis shows

We might also

turn this hypothesis on its head and argue …

Turning a hypothesis on its head only occurs once in this search, but turn@+3on+its+head reveals 25 concordances.

False friends

The internet will provide you with many pages of false friends: try an internet search on “false friends” English plus the name of another language into a search engine. Or click on Confusing Words to go to a list of words that are alike in various languages.

Practice makes perfect

So you think you know the parts of the body in English. Well, you probably do. But do you know what amazing things they can do or how they are described and referred to? Try this matching activity and then check your answers using CCS. You might like to add some other verbs beside each noun.

|

Nouns |

Verbs |

|

shoulders |

pick |

|

eye |

wag |

|

heart |

lick |

|

throat |

grind |

|

finger |

blink |

|

nose |

gargle |

|

buttocks |

shrug |

|

neck |

pound |

|

lips |

crane |

|

teeth |

clench |

Now find out which of the nouns can be used as verbs. For example, can one eye something, head something, mouth something or shoulder something? Search query: thumb@/VERB.

Can you match these? Can the concordancer help?

|

Adjectives |

Nouns |

|

accusing |

shoulders |

|

greasy |

thumb |

|

limp |

lips |

|

curvaceous |

neck |

|

hunched |

finger |

|

green |

nose |

|

stiff |

buttocks |

|

parted |

wrist |

|

pointy |

palm |

How are these words used metaphorically?

|

Nouns |

Use |

|

a shoulder of |

burden |

|

the eye of |

music |

|

to shoulder the |

lamb |

|

an ear for |

stone |

|

nerves of |

a story |

|

a nose for |

steel |

|

heart of |

the storm |

Metaphor is a fundamental aspect of communication. Many high frequency words are used in many different ways, which is partly why they are so frequent, and an aspect of their use that learners need to become familiar with. For more on this, you could read metaphors, an extract from Metaphors We Live By (Lakoff and Johnson, 1980)

Can you find parts of the body words used in idioms or other fixed phrases?

What about this: grin@+3grin@ or the same search on smile

or look

10. Further study

These sessions have been principally

concerned with training you in an approach to accessing the GRAMMAR OF

VOCABULARY you need when you need it.

A lot of current work in language and linguistics, including that relevant to learning foreign languages, gives preference to the structural elements of vocabulary over sentence grammar.

As far as concordancing is concerned, there are still many more things you can do with the CCS. And the CCS is not the only concordancer on the net. And the Collins Cobuild Corpus Sampler is not the only concordancer on the net. Firstly, there is the full Collins Wordbanks online, from which the Sampler is derived.

Some others are listed below and there are some available for purchase on CD, though not all of them have corpora included. As you read through the sites linked below, you will see other activities and approaches, and of course, other links!

It is possible to create your own corpus, though this is beyond the realm of this particular website. If you this is of interest to you, read Improvising corpora for ELT: quick-and-dirty ways of developing corpora for language teaching by Christopher Tribble and The Learner as Corpus Designer by Guy Aston. Obtaining copyright permission to use texts is a complex issue and corpora based on out-of-copyright data cannot represent a language in its current state.

The World Wide Web Access to Corpora Project (W3-Corpora) was run at the Department of Language and Linguistics at the University of Essex. Click their tutorial for the W3-Corpora Interface to access their corpus and concordancer. Although it works differently from the CCS, you will experience such practical things as:

·

looking for the meaning of a word

· comparing two similar words/synonyms

· comparing how a word is used in different kinds of text

· seeing which preposition to use

· checking the spelling of a word

which you can apply and add to your repertoire of techniques.

Corpora have been constructed in many languages. For a list, look Mike Barlow’s list.

An important practical issue for the language learner: what do you do with the answers to your questions? Tom Cobb has written about this: Giving learners something to do with concordance output.

Some Resources

The home

page of Tim Johns of Data Driven

Learning fame contains a wealth of original material and links.

Mike Scott co-authored Microconcord (a DOS concordancer with 2 million corpus – still good and fast) with Tim Johns and then the more sophisticated Wordsmith Tools (for Windows).

Tom Cobb’s article, Breadth and depth of lexical acquisition with hands-on concordancing, describes an experiment using concordancing with students who needed to acquire a large vocabulary quickly.

Tom Cobb’s The Compleat Lexical Tutor includes a range of applications of corpus work to vocabulary teaching. An article by him about using concordance software to provide learners with a rich language learning experience can be found at Concordancing in the CEGEPs.

Spaceless: This concordancer takes the text of a web page and creates a list of sentences that contain the search term.

The VLC Web Concordancer (the Virtual Language Centre) provides basic concordance search and retrieval functions using corpus files which are located on the VLC server.

Corpora in the Teaching of Languages and Linguistics by Tony McEnery and Andrew Wilson contains the authors’ summary of their book.

Vance Stevens’ article: Concordancing with Language Learners: Why? When? What?

Gregory Handley describes his experiment introducing Data Driven Learning with his Japanese students in Sensing the Winds of Change.

If you would like to look into concordances and corpora more deeply, try this tutorial by Catherine N. Ball.

Click here for the University of Stirling’s Introducing the concordance site.

Click here for an overview of The Use of Corpora in Language Studies.

Ø Glossary of terms used in concordancing literature

Ø Using computers in Linguistics glossary

The End

© James Thomas 2002